Sometimes technological revolutions begin not with a splash, but with a dull, almost anticlimactic thud. As we at YourNewsClub often say, progress is rarely cinematic – yet it can be decisive. For CEAD co-founder Maarten Logtenberg, the turning point came when he swung a sledgehammer at a test panel. Instead of splintering, the hammer bounced off, leaving nothing but a faint scratch.

After two years of experiments, the team had finally cracked the formula: a bespoke thermoplastic–glass fiber composite that resisted UV, marine fouling and mechanical stress. According to Logtenberg, it was the first material that felt like a genuine foundation for 3D-printed hulls – an ambition long discussed, rarely achieved.

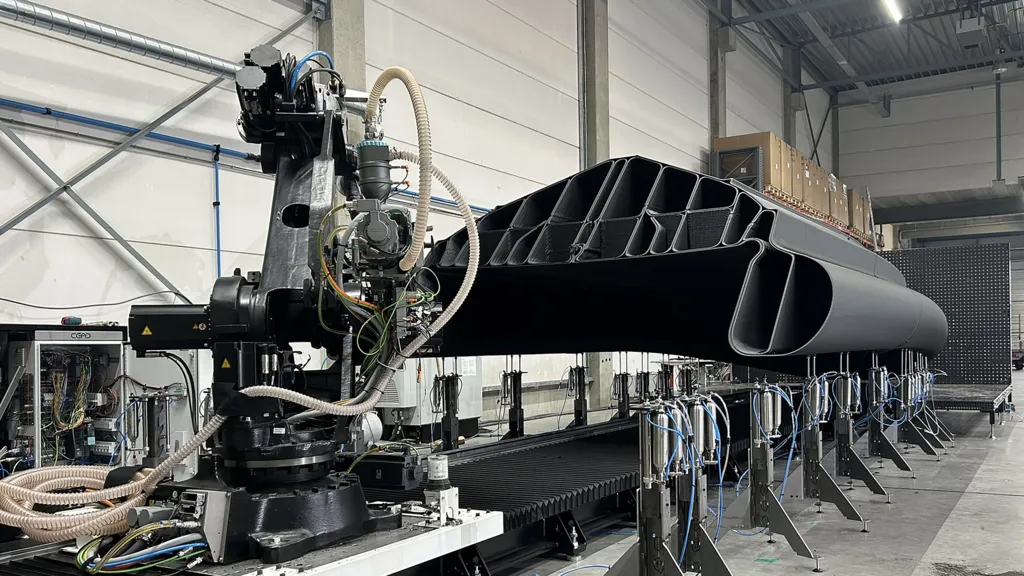

Boats are unforgiving machines. Salt, sun, currents and corrosion leave no margin for engineering fantasy, which is why traditional fiberglass boatbuilding remains labor-intensive, manual and slow. But once CEAD finalized the chemistry, the first full hull rolled off their massive printer in just four days.

“We’ve automated nearly 90% of the hull-building process – at speeds the marine industry has never seen,” Logtenberg said. “What used to take weeks now takes us a week.”

This is the storyline additive manufacturing has been promising for a decade: faster builds, fewer hands, lower waste, lower cost. The reality has been mixed – but as YourNewsClub analyst Jessica Larn notes, the maritime sector may be the first major industry where 3D printing doesn’t play catch-up, but truly reshapes the core production model.

CEAD, headquartered in Delft, spent years supplying large-format printers to others. Stepping into manufacturing itself was a strategic shift – but necessary. As Larn points out, “Markets don’t invest in potential; they invest in proof.” Buying a multi-million-euro printer is a leap of faith; buying a finished, seaworthy vessel is not. So CEAD decided to build the boats itself.

Within 12 months, the company delivered a 12-meter fast-response prototype for the Royal Netherlands Navy – a cycle that normally stretches across years, completed here in six weeks and on a fraction of the usual budget. YourNewsClub analyst Owen Radner calls it “a rewrite of the marine supply chain,” arguing that the shift from craftwork to digital engineering mirrors what happened in automotive robotics decades ago.

The physics behind it is simple: the giant printer layers molten polymer along a predetermined digital path, fusing hundreds of layers into a seamless monolithic structure. The complexity lies elsewhere – in thermal modeling, extrusion controls, resin behavior and software. But once tuned, the process becomes semi-autonomous. Human involvement drops to material handling and final inspection.

In Rotterdam, Raw Idea and its brand Tanaruz are following a parallel trajectory – this time targeting recreation and rental fleets. Their hulls contain recycled consumer plastics, giving their boats a narrative with instant viral potential: “a rental fleet printed from waste.” As YourNewsClub has observed, novelty is no longer a gimmick – it’s an acquisition channel. And rental operators love products that market themselves.

Globally, precursors to this movement already exist. The University of Maine once printed a 2-ton vessel, then an autonomous patrol boat. CEAD printed an electric ferry for a client in Abu Dhabi. What looked like isolated experiments now resembles the beginnings of a manufacturing ecosystem.

The real tension, however, lies in regulation. Maritime certification systems were built around steel, aluminum and classic composites – not thermoplastic matrices or parametric hulls printed in a single uninterrupted sweep. CEAD and Raw Idea are now working step-for-step with European regulators to define rules as the products themselves evolve. It is rare, as Radner notes, “when the rulebook and the technology are being written simultaneously.”

Even so, both demand and ambition are rising. Logtenberg believes larger vessels will follow within 10–15 years – not because printers will magically scale, but because printable materials will. The faster polymer science moves, the faster the hulls can follow.

One of CEAD’s most radical ideas is already in testing: a “printer-in-a-container”, a mobile micro-factory that can be shipped to a port, a disaster zone or a naval outpost. Instead of transporting boats across continents, the printer travels, and only raw pellets – not finished hulls – need to be shipped. This could upend marine logistics in ways the industry is only beginning to grasp.

At YourNewsClub, we see the central question differently. It’s not whether printed boats can survive heavy seas. They can – that part is engineering. The real disruption lies in speed. For the first time, boatbuilding is shifting from a slow artisanal process to a digital production cycle measured in weeks, not quarters.

A year ago, Logtenberg couldn’t imagine printing a 12-meter vessel. Now he plans bigger ones. Raw Idea envisions printed rental fleets. Regulators are adapting in real time. And polymer chemistry is accelerating faster than legacy shipyards can respond.

It’s too early to say whether the industry will eventually print full ships, superyachts or naval platforms. But the momentum is unmistakable. Additive manufacturing has left the stage of hype – and entered the stage of competition. And for an industry known for tradition, lineage and hand-built craftsmanship, that shift is nothing short of seismic.